The United Snakes in Africa

Politicians, Prostiticians, and The Ghana-United States Military Base Agreement:

What happens when you let the united snakkkes into your home?

by Ọbádélé Kambon and Nana Yaw Mireku Yɛboah, University of Ghana

Abstract: In this paper, we reject the argument put forward by some stakeholders that the United States is not actually establishing a military base in Ghana by utilizing the U.S. Department of Defense’s own definition of “base”.

Then, we demonstrate point for point how the agreement fits every aspect of the definition of a base via textual analysis. We then present research on how the u.s. routinely violates treaties, pacts and agreements focusing on two case studies: the 1993 Chemical Weapons Convention and the 1963 Vienna Convention on Consular Relations (Koplow, 2013).

We demonstrate that the u.s. does not keep its word and that this tradition continues with Donald Trump, though it certainly did not start with him. We conclude with the significance of US treaty violations as a whole and, in the broader context of bargaining with a demonstrably unilateral rogue nation like the United States, the significance for Ghana, her people and her future using [Oscar] Brown [Jr.] and [Al] Wilson’s song “The Snake” as the basis for our conceptual framework introduced here.

Introduction and Background

In this article, we will implement a textual analysis of the Ghana-US Military Base agreement. On March 28, 2018, Ghana’s Parliament ratified a military cooperation agreement between Ghana and the USA. This touched off a media firestorm whereby sections of the Ghanaian public took the view that such an agreement is a significant compromise of Ghana’s sovereignty, and dignity for that matter.

Some of the initial questions that came up in the media at that time were related to whether or not what was being proposed was actually a military base or not. The Communications Bureau of the Presidency also issued an official statement by President Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo entitled “No US Military Base In Ghana” stating “the United States of America has not made any request for such consideration and, consistent with our established foreign policy, we will not consider any such request” (Bureau, 2018).

According to Collins English dictionary, a military base in British English is simply defined as “a facility for the storage of military equipment and the training of soldiers” (HarperCollins, 2018). According to Cambridge, a base [noun (MILITARY)] is defined as “a place where there are military buildings and weapons and where members of the armed forces live.” (Press, 2018).

While these definitions are useful for general English, in our opinion, the most accurate and pertinent definition of a military base in the current context is that provided by the dictionary of the US Department of Defense, which specifically provides definitions of military and associated terms.

The dictionary “supplements standard English-language dictionaries and standardizes military and associated terminology to improve communication and mutual understanding within DOD with other US Government departments and agencies and among the United States and its allies” (Staff, 2018, p.1). We will return to this point on ‘allies’ because apparently, we Afrikans=Black people do not understand the meaning of ‘allies’ to the u.s. nor do we fully comprehend how the u.s. treats its allies.

The dictionary of the US Department of Defense is that of September 2018, so it is very current. According to the dictionary of the Department of Defense of the United States, a base is explicated by way of a tripartite definition as

1. A locality from which operations are projected or supported.

2. An area or locality containing installations which provide logistic or other support.

3. Home airfield or home carrier. (Staff, 2018, p. 25)

Methodology

Using this definition, by way of methodology, we will engage in a thorough textual analysis in terms of how the proposed u.s. military base in Ghana fits each of these three criteria as outlined by the Joint Chiefs of Staff/US Department of Defense. Upon establishing that, indeed, we are dealing with a military base, we will go into the potential dangers of allowing a criminal organization like the u.s. the opportunity to gain a foothold in Ghana given their longstanding track record of acting unilaterally and with impunity. To this end, two case studies will be framed within a historical context whereby the precedents of unilateralism and non-adherence to pacts, treaties and agreements are considered.

“The Snake”: A Novel Conceptual Framework for Understanding Ghana’s Acceptance of the US Military Base Deal

On 23 March 2018, despite the controversy, Ghana’s Parliament approved the MBA deal (Allotey, 2018). To understand the implications of this decision, we here present Brown and Wilson’s lyrics to “The Snake” in our creation of a conceptual framework based upon the song:

On her way to work one morning

Down the path alongside the lake

A tender-hearted woman saw a poor half frozen snake

His pretty colored skin had been all frosted with the dew

“Oh well,” she cried, “I’ll take you in and I’ll take care of you”

“Take me in oh tender woman (come on in)

Take me in, for heaven’s sake (come on in)

Take me in, for heaven’s sake

Take me in tender woman,” sighed the snake

She wrapped him up all cozy in a coverture of silk

And then laid him by the fireside with some honey and some milk

Now she hurried home from work that night as soon as she arrived

She found that pretty snake she’d taken in had been revived

“Take me in, oh tender woman (come on in)

Take me in, for heaven’s sake (come on in)

Take me in tender woman,” sighed the snake

Now she clutched him to her bosom, “You’re so beautiful,” she cried

“But if I hadn’t brought you in by now you might have died”

Now she stroked his pretty skin again and then kissed and held him tight

But instead of saying thanks, that snake gave her a vicious bite (oh…)

“Take me in, oh tender woman (come on in)

Take me in, for heaven’s sake (come on in)

Take me in tender woman,” sighed the snake

“I saved you,” cried that woman, “And you’ve bit me even, why?

And you know your bite is poisonous and now I’m gonna die!”

“Oh, shut up, silly woman,” said the reptile with a grin

“You knew damn well I was a snake before you brought me in

“Please take me in, oh tender woman (come on in)

Take me in, for heaven’s sake (come on in)

Take me in tender woman,” sighed the snake

Sighed the snake

“Take me in, tender woman”

Sighed the snake, sighed the snake

“Take me in, tender woman”

Sighed the snake

(Oscar Brown Jr. & Al Wilson, 1968) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2Vjfw7UHl_E

Using this concept, we argue that Ghana’s apparent ignorance of the nature of “The Snake” or, in this case, the united snakkkes, will inevitably lead to the host being viciously bitten. Given what we know of the united snakkkes government and its imperatives to operate on the basis of unilateralism and impunity, we argue that the approval of this deal is tantamount to inviting a snake into one’s home. And as a proverb in Kiswahili states: Amletae nyoka nyumbani akili zake hazimo kichwani. ‘One who brings a snake home has a head without brains.’

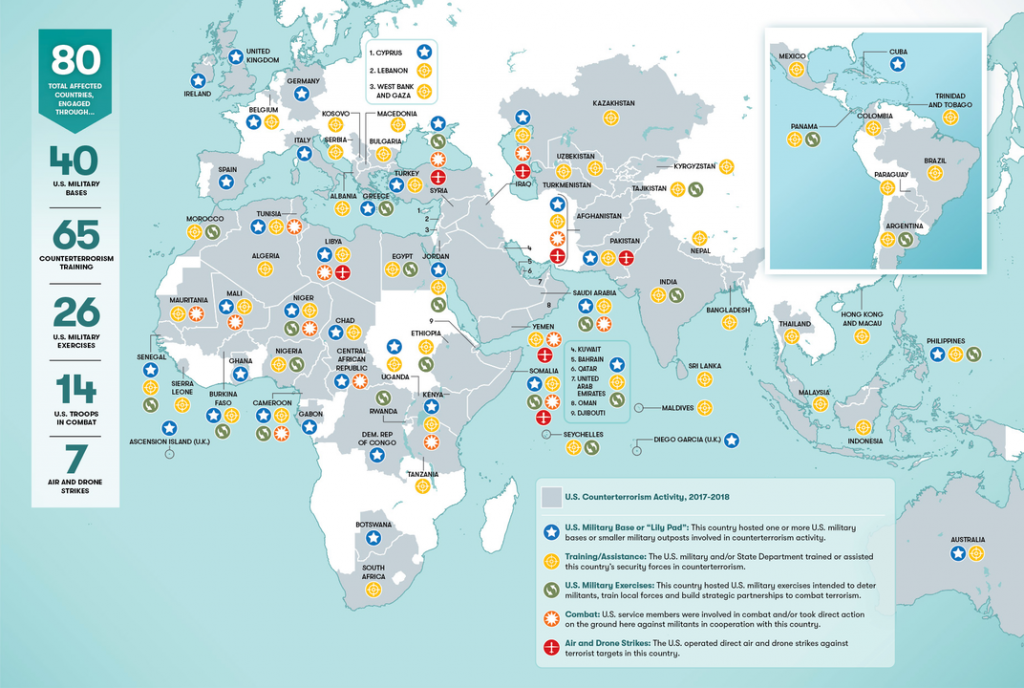

The oldest known attestation of the term “United Snakes” dates back to 1902, though the use of snake symbolism to describe what would eventually become known as the United States of America dates back to at least 1754 as used in Benjamin Franklin’s “Join, or Die” political cartoon (Corrothers, 1902, p. 73; Franklin, 1754).

In more recent times, both Brother Diablo and Amiri Baraka also referred to the US as the “United Snakes”, while the use of the term in scholarly writing can be found as recently as 2016 (Baraka, 1978, p. 330; James, 1972; Moore, Gray-Garcia, & Thrower, 2016).

The earliest known attestation of the stylized variation we are using here, i.e. lowercased and with three (3) ks, an allusion to the ku klux klan terrorist organization, dates to 2007 (Otto, 2007).

In this paper, we are using the term as part of the Brown & Wilson-derived conceptual framework of what happens when one invites a snak[kk]e into one’s home (O. Brown & Wilson, 1968). Ancestor Baba Ọmọ́wálé (a.k.a. Malcolm X) stated “Of all our studies, history is best qualified to reward our research” (X, 1963).

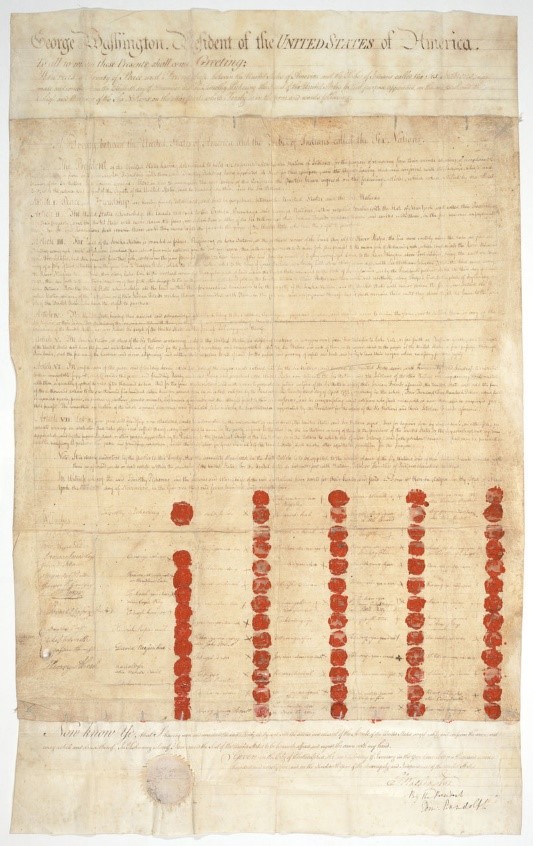

This history of unilateralism and impunity of the united snakkkes is not new. Indeed, “The U.S. federal government entered into more than 500 treaties with Indian nations from 1778 to 1871; every one of them was ‘broken, changed or nullified when it served the government’s interests’” (Deloria Jr, 2010; Egan, 2000; Toensing, 2013).

The united snakkkes could, at any time, choose to honor these treaties – which are still in effect under u.s. law – but chooses not to do so; rather the united snakkkes chose and continues to choose to operate with unilateralism and impunity vis-à-vis those who do not have the power to enforce their will.

What does this tell us about Ghana’s chances if and when the united snakkkes decides to bite? We argue that those who objected to the deal are the ones who may have a greater awareness of this history, while those making these decisions are either blindly obtuse to these historical precedents or they simply do not care about their people being “bitten”.

Again, with that in mind, we have to go into basically the rhetorical ethic which the united snakkkes has always operated on. Mama Marimba Ani defines the rhetorical ethic as follows:

“Culturally structured European hypocrisy. It is a statement framed in terms of acceptable moral behavior towards others that is meant for rhetorical purposes only. Its purpose is to disarm intended victims of European cultural and political imperialism. It is meant for “export” only. It is not intended to have significance within the culture. Its essence is its deceptive effect in the service of European power (Ani, 1994, pp. xxv-xxvi)

Put quite succinctly, they say one thing and do otherwise. The rhetorical ethic is the core of the united snakkkes hypocrisy not as deviation, but as a fundamental way of life whereby one can say that we are all equal but at the same time enslave Afrikan=Black people.

How the terms of the Ghana-US Military Base Agreement are Consistent with the US DoD Definition of a Military Base

In this section, we will directly draw from the text of the leaked military base agreement itself in order to establish beyond any reasonable doubt that US is indeed establishing a military base according to the definition given by the dictionary of the Department of Defense of the U.S. : Locality from which operations are projected or supported / An area or locality containing installations which provide logistic or other support.

In the preamble to this Military Base Agreement (MBA), it says the “United States forces may be present in Ghana in pursuit of common defence efforts, as well as to provide support to the security of United States Government personnel and facilities in the regions” (Graphic.com.gh, 2018). This clearly speaks directly to definition (1) whereby Ghana would be used for projecting or supporting US operations as well as (2) in which Ghanaian soil will serve as the area or locality containing installations providing logistic or other support (Staff, 2018).

In article 2 of the MBA, points (2) and (3) states that:

“2. This Agreement clarifies access to and use of agreed facilities and areas by United States forces, thereby facilitating training, including to maintain unit readiness, combined exercises and other military engagement opportunities.

“3. United States forces may undertake the following types of activities in Ghana: training, transit, support and related activities; refueling of aircraft, landing and recovery of aircraft, accommodation of personnel, communications, staging and deploying of forces and materiel; exercises, humanitarian and disaster relief and other activities as mutually agreed.”

These points of the MBA, again, are unambiguous in terms of their relation to definitions (1) and (2) as they directly address the operations and logistic support role to which Ghana would be bound.

Along the same lines, the MBA also unequivocally states in Article 7 that:

“United States forces are hereby authorised to preposition and store defence equipment, supplies and materiel (hereinafter referred to as prepositioned materiel) at agreed facilities and areas. The prepositioned materiel of United States forces and the agreed facilities and areas or portions thereof designated for storage of such prepositioned materiel shall be for the exclusive use of United States forces. United States forces shall retain title to and control over the use of prepositioned material and shall have the right to remove such items from the territory of Ghana.” (Graphic.com.gh, 2018)

Again, this goes to the heart of logistic and other support. In other words, the u.s. can bring in “prepositioned materiel” and take it out of Ghana unilaterally while Ghana cannot do anything about it in protest or otherwise. Indeed, this is exactly what we should expect from a u.s. military base.

Article 11 also relates the same point in terms of logistics and other support in that it says that:

“United States forces may import into and export out of and use in Ghana any property equipment, supplies, material, technology, training, or service in connection with this agreement. Such importation, exportation and use shall be exempt from any inspection, license, other restrictions, customs duties, taxes or any other charges assessed within Ghana.” (Graphic.com.gh, 2018)

So basically, the u.s. military is able to act with impunity according to this agreement while Ghana has signed away its avenues of recourse in this strait jacket of an agreement. This point is driven home in Article 6, which states that although buildings constructed will be regarded as Ghanaian property formally, they “[…] shall be used by United States forces until no longer needed by United States forces” (Graphic.com.gh, 2018).

In other words, if you own a car, but I have taken it from you and can use it for however many years I want until I decide that I do not want it anymore, what does it truly matter whether I allow you to hold onto ownership papers or not in the meanwhile? Indeed, this language is very much consistent with what would be expected for a military base in keeping with the DoD’s definition of just such a base. Again, in Article 14 of the MBA, we find that Ghana is beholden to allow the US military “…Use of the radio spectrum” which “shall be free of cost to United States forces” (Graphic.com.gh, 2018). This relates directly to the question of logistics and operations support.

Home airfield or home carrier

We will now turn our attention to the third part of the definition of a military base, which is given as “a home airfield or home carrier” (Staff, 2018). According to Article 12 of the MBA, it states that: “Aircraft, vehicles and vessels operated by or, at the time, exclusively for United States forces may enter, exit and move freely within the territory and territorial waters of Ghana” (Graphic.com.gh, 2018).

This clause is the clearest abdication of Ghana’s sovereignty discussed thus far. Indeed, as worded, there is absolutely no limit upon this free movement stated implicitly or explicitly. Indeed, this is tantamount to a severely compromised immune system whereby anything can enter and the T-cells cannot do anything to prevent germs, viruses, bacteria, etc. According this same article, it states that:

“Aircraft, vehicles and vessels operated by or, at the time, exclusively for United States forces shall not be subject to the payment of landing, parking or port fees, compulsory pilotage, navigation or over flight charges; or tolls or other use charges; however, United States forces shall pay reasonable charges for services requested and received at rates no less favorable, less taxes and similar charges, than those paid by the Armed Forces of Ghana.” (Graphic.com.gh, 2018)

Article 12 further states that:

“United States Government aircraft, vehicles and vessels shall be free from boarding and inspection without the consent of United States forces authorities.” (Graphic.com.gh, 2018)

Further, it is stated that:

“Ghana hereby provides unimpeded access to and use of agreed facilities and areas to United States forces, United States contractors and others as mutually agreed. Such agreed facilities and areas or portions thereof, provided by Ghana shall be designated as either for exclusive use by United States forces or to be jointly used by United States forces and Ghana. Ghana shall also provide access to and use of a runway that meets the requirements of United States forces.” (Graphic.com.gh, 2018)

In other words, essentially anything the u.s. would be able to do with “a home airfield or home carrier” on mainland u.s. soil is what they will be able to do on erstwhile Ghanaian soil.

Therefore, we have demonstrated that according to the Joint Chiefs of Staff’s dictionary of the Department of Defense of the united snakkkes, the military base conforms to each of the three aspects of the definition of a military base including the provision of military logistics support, projecting and supporting operations, and serving as a home airfield or home carrier for aircraft.

In the words of Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo, “Ghana has not offered a military base, and will not offer a military base to the United States of America” (AFP, 2018). He further stated that “I will never be the president that will compromise or sell the sovereignty of our country. I respect deeply the memory of the great patriots whose sacrifice and toil brought about our independence and freedom” (AFP, 2018).

However, perhaps due to his unfortunate misunderstanding of what constitutes a military base, he may not be aware that this is exactly what he has just done. Further, in addressing the question of sovereignty with regard to territorial integrity and self-defense, Article 5 states that:

“United States forces are hereby authorized to exercise all rights and authorities that are necessary for the use, operation, defense, or control of agreed facilities and areas, including taking appropriate measures to protect United States forces. United States forces intend to coordinate such measures with the appropriate authorities of Ghana” (Graphic.com.gh, 2018).

This means that if (perhaps under pretense), the u.s. decides that there is the need to protect the united snakkkes forces, they are authorized to do so according to their own discretion as they deem appropriate. While the last sentence relates to an intent to coordinate measures with the appropriate authorities of Ghana, this is, once again, left to the discretion of u.s. intent.

The united snakkkes has a Military Base in Ghana: So What?

We will now turn our attention to why anyone, specifically a Ghanaian, should care about the united snakkkes military base that will be firmly planted in the soil of the country. In this section, we will provide a background on the u.s. track record for acting unilaterally and with impunity.

Indeed, unilateralism has been the de facto policy of the united snakkkes since before the time of George Washington to present. As we will discuss below, the u.s. entered into over 500 still-legally-binding treaties with its indigenous people and breached each one of them.

When it comes to bargaining with a unilateral rogue nation like the u.s., John Jay back in 1788 candidly stated in Federalist Paper No. 64, “that a treaty is only another name for a bargain, and that it would be impossible to find a nation who would make any bargain with us, which should be binding on them absolutely, but on us only so long and so far as we may think proper to be bound by it” (Alexander, James, & John, 1788).

This is the essence of unilateralism. Unilateralism refers to doctrinal adherence to one-sided action in disregard for other parties regardless of agreement or disagreement of other affected stakeholders. In this instance, it refers to the united snakkkes’ tendency to move in its own interest without consulting Ghana or any other party who would be potentially adversely affected by that pursuit.

In the 1796 farewell address of George Washington (the first President of the United States), he stated unequivocally that; “It is our true policy to steer clear of permanent alliances with any portion of the foreign world” (Washington, 1796, p. 9). It should be noted that this stance was taken long before that of UK’s Lord Palmerston’s 3 March 1831 speech in the House of Commons, where he stated:

“Therefore I say that it is a narrow policy to suppose that this country or that is to be marked out as the eternal ally or the perpetual enemy of England. We have no eternal allies, and we have no perpetual enemies. Our interests are eternal and perpetual, and those interests it is our duty to follow” (Francis, 1852, pp. 172-173)

A similar sentiment, was echoed by Thomas Jefferson who stated in his first inauguration speech of 4 March 1801, “peace, commerce, and honest friendship with all nations, entangling alliances with none” (Jefferson, 1801).

Henry Alfred Kissinger, a u.s. war criminal, who served as United States Secretary of State and National Security Advisor, is noted to have quipped that “America has no permanent friends or enemies, only interests.” (St Pierre, 2014, p. 9).

This means if we think we are entering into a genuine bilateral alliance with the united snakkkes, we are dreaming, as their articulated thoughts, words, and deeds tell Afrikans=Black people that they are going to act unilaterally in their own interests even or especially if that goes against the interest of Afrikan=Black people.

In the case of Ghana, we may sign the treaty, but if the u.s. decides unilaterally it has no interest in honoring its word, we have no recourse – whether legal, military, or anything else to get these united snakkkes off of our soil; indeed, that soil is not our soil anymore because according to the agreement they can use it as long they deem necessary. Again, as Ghanaians, we have to understand the type of reptile we are dealing with when it comes to the united snakkkes and the unilateral impunity with which it operates.

The question is, what do we anticipate that Ghana is capable of doing if the united snakkkes decides to unilaterally violate any of the terms of the military base agreement which, as we have noted, were already drawn up in its favor?

What will Ghana be able to do that not even the International Court of Justice, the UN General Assembly and the UN Security Council are able to accomplish whenever the u.s. decides to act with the unilateral impunity so characteristic of its snakkke-like nature? If the united snakkkes unilaterally decides to foment a coup d’etat against the President of Ghana, as the CIA did in the case of the 1966 coup, who will we be able to call for help; The UN? The UN cannot even get the u.s. to pay its dues, much less can they do anything if the united snakkkes decides to act unilaterally and arbitrarily against Ghana and Ghanaian interests with impunity.

Military bases, such as the one that the united snakkkes is coming to establish, are very difficult to get rid of once established. This is something that must be kept in mind if and when things start to go in a direction that is not beneficial to Ghana. Throughout the world, many of the u.s. military base agreements were signed many decades ago. According to Stephan Roget,

“Many of the US military bases, or at least the agreements behind them, were established many decades ago. Of course, some of the host countries have since changed their mind a bit when it comes to allowing a constant American presence within their borders.

“Unfortunately for them, once the relationship has begun, it is difficult to get out of. For a country to remove an American base from their soil, they must risk greatly damaging their diplomatic relations with the US. They can even risk a military response if the Americans value the location enough. For most, it is not even close to worth it.” (Roget, 2018)

Two (2) Case Studies of united snakkkes Unilateralism and Impunity

In this section, we will build our foundation to make it crystal clear that if Ghana thinks that the united snakkkes will honor its agreements, history shows demonstrably that this is simply not the case. The u.s. has a track record of not honoring its treaties, agreements and/or pacts. Thus, we are establishing a history of the united snakkkes not doing what it says that it will do. While the more remote historical context is useful to frame the discussion, a few more recent historical precedents are articulated in an article titled “Indisputable Violations: What Happens When the United States Unambiguously Breaches a Treaty” (Koplow, 2013).

In the article, it states that:

“On multiple occasions, the United States has joined a valid treaty, helped bring it into legal force, accepted the obligations and the benefits that come with it, and then unarguably and ostentatiously violated the treaty. As detailed in the two cases below, the United States has a history of flatly breaching commitments and, when challenged, having nothing to assert in its defense.” (Koplow, 2013)

It is very likely that no one in the Presidency or Parliament of Ghana has researched into how the united snakkkes routinely violates its treaties with others; however, as researchers, it behooves us to make this information known to well-meaning Ghanaians in good faith. In Koplow’s (2013) aforementioned article, he brings illustrative case studies of blatant united snakkkes violations of binding international legal obligations: the 1993 Chemical Weapons Convention and the 1963 Vienna Convention on Consular Relations. In all cases, the united snakkkes breaches the international rule of law and treaties onto which it has signed.

The Chemical Weapons Convention

We will begin with the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC). The treaty states that parties to the CWC will commit to

“never develop, produce, acquire, retain, transfer, or use chemical weapons and to destroy their existing stockpiles. The treaty lays out a timetable for the elimination of existing weapons called the “order of destruction” with interim benchmarks until the tenth year. By then, each party must have incinerated, chemically neutralized, or otherwise destroyed 100 percent of its declared chemical weapon inventory.” (Koplow, 2013, p. 56).

The CWC entered into force on April 29, 1997 and made April 29, 2012, the absolute final deadline for completing the complete destruction of all chemical weapons built up during the cold war; this period made provisions for a single allowable five-year extension (Koplow, 2013, p. 57).

However, as we can expect from those who make hypocrisy a way of life, the united snakkkes has not lived up to its part of the bargain.

With regard to the Chemical Weapons Conventions, not only did the united snakkkes fail to accomplish the destruction of their stockpiles of chemical weapons, but that it will take until the fourth quarter of 2023 – some eleven and a half years beyond the supposedly “final” date to eliminate the remainder of the chemical weapons. It should be noted that this leaves open the possibility of the snakkkes “biting” Ghana using some portion of the remaining stockpiled chemical weapons on the basis of any pretense or simply because this is what happens when you invite the united snakkkes into one’s home.

The Vienna Convention on Consular Relations

In the 1963 Vienna Convention on Consular Relations (VCCR), Article 36 stipulates that “when a party arrests, imprisons, or detains a foreign citizen, it must inform him without delay of his right to have his consul notified of the adverse action and to communicate with his home authorities” (Koplow, 2013, p. 59). The united snakkkes exercises its right emanating from the Vienna Convention on a daily basis. In 2010 alone, amerikkkan consular officers conducted 9,500 prison visits throughout the world and assisted 3,500 u.s. citizens arrested abroad (Koplow, 2013). Most notably, “the VCCR formed a critical part of the U.S. legal action against Iran after the seizure and detention of American embassy personnel in Tehran during the hostage crisis of 1979-1981” (Koplow, 2013, p. 60). However, snakkkes that they are, they do not show reciprocity when it comes to VCCR rights.

According to Koplow, “When U.S. law enforcement authorities arrest or detain foreign nationals, they fail dozens of times annually, to advise them of their rights and to notify the appropriate consuls” (Koplow, 2013, p. 60). Often, the foreigner is tried, convicted, sentenced, and incarcerated or executed before anyone notices or even cares that the VCCR may be relevant. On numerous occasions, the ICJ ruled that the united snakkkes had clearly violated the treaty. However, punishment for these violations is never forthcoming. After all, what can one expect after a bite from the united snakkkes other than an admission that “It’s my nature” (Heer, 2016; Trump, 2012).

Other Recent Unilateral Treaty Violations and/or Withdrawals

It is important to keep in mind, at this juncture, that this is not a question of whether or not the united snakkkes is bad all the time or is good all the time, it is a question of what its fundamental nature is, as exhibited through its behavior over the course of space and time. This is the moral of “The Snake” in his exclamation “You knew damn well I was a snake before you brought me in!” (O. Brown & Wilson, 1968).

This same unilateral nature was evinced when the u.s. put its unilateral interests before multilateral consideration when it withdrew from the International Coffee Agreement of 2007 in alignment with amerikkka’s [white] nationalist agenda put forward by Donald Trump (N. Brown, 2018; TeaandCoffee.com, 2018).

Another BBC news article of June 20th 2018, states that the “US quits ‘biased’ UN human rights council” in another exemplification of an all-too-familiar pattern (BBC, 2018). From this, we ask the question of who can hold the united snakkkes responsible after laying the united snakkkes by the proverbial “fireside with some honey and some milk” (O. Brown & Wilson, 1968).

Again, we can see an earlier instance of this type of behavior with wide-reaching implications when Trump pulled out of the Global Climate Change Pact, also known as the Paris Agreement (Geggel, 2018).

So, we can clearly see that the united snakkkes will sign pacts and agreements, only to unilaterally act in its interests, whether or not those interests may have a deleterious impact on other countries or the planet itself. Trump’s unilateralism is far from a break with tradition, but is rather a continuation of it.

In the future we can expect more of the same, given that “Donald Trump can unilaterally withdraw from treaties because congress abdicated responsibility” (Feingold, 2018). All of the aforementioned instances of unilateralism go to establishing a timeline of precedents of an open door to not honoring any treaty that the u.s. signs onto as envisaged by John Jay and other hatchlings of the united snakkkes (Alexander et al., 1788).

So why does it all matter anyway? As Koplow (2013) writes:

“Why does it matter that the United States violates treaties, and occasionally does so without a shred of legal cover? Perhaps that is the realpolitik privilege of the global hegemon: to be able to sustain hypocrisy[…] [I]ts “exceptional” position in the world enable[s] the United States explicitly to welch on its debts, fudge on its obligations, and adopt a “do as we say, not as we do” approach with other countries. (pp. 68-69)

In other words, the united snakkkes wants to hold others to terms to which it does not submit. So why would someone enter into an agreement on those types of terms? In our view, there are several Vectors of Compromise that may play a role in the decisions of what we term “prostiticians” to compromise and sell out. The naming and analysis of these vectors of compromise were first developed here: Kambon, O., & Yɛboah, R. M. (2018). Haiti, Morocco and the AU: A Case Study on Black Pan-Africanism vs. anti-Black continentalism. CODESRIA: Identity, Culture, And Politics 19(1-2), 41-64. Retrieved from https://www.codesria.org/spip.php?article3039&lang=en. The vectors are not mutually exclusive, including, but not limited to, the following:

Vectors of Compromise of anti-Black=anti-Afrikan Prostiticians/Pimp-liticians

1. The Financial/Created Tastes and Desires Vector

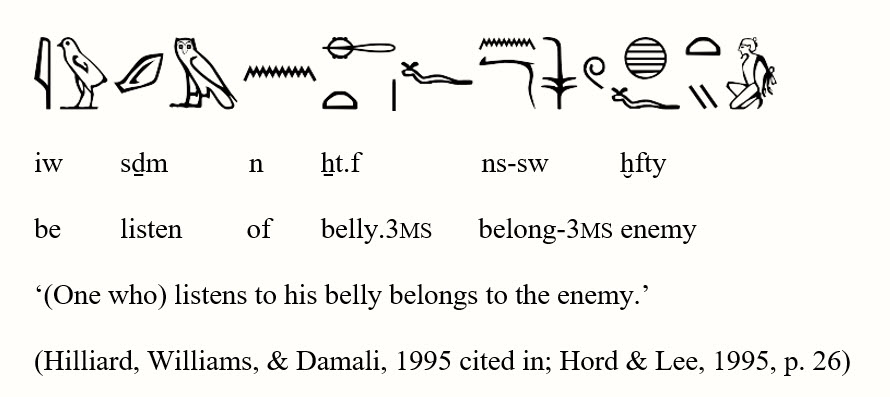

The financial/created tastes and desires vector is straightforward in terms of selling out in that someone simply pays the sell-out in cash or in kind and in exchange they treasonably sell out Afrikan=Black causes, goals, aspirations, and lives. The oldest book in the world, the instructions of Ptahhotep:

“(One who) listens to his belly belongs to the enemy.” (Hilliard, Williams, & Damali, 1995 cited in; Hord & Lee, 1995, p. 26)

This sentiment was echoed later by Nana Thomas Sankara who said “He who feeds you, controls you” (Shuffield, 2006). Along similar lines, Nana Amos N. Wilson (1992) stated:

“If we look at our behavior, we will see that to a good extent, it is our behavior, our values, our consciousness, the kind of personalities we’ve established in ourselves, our taste, our desires and needs; that maintains the European in its position” (p. 5).

2. The Biogenetic Vector-The Mulattofication of Afrikan=Black interests

The biogenetic vector is what Nana Dr. Chancellor Williams refers to as the mulatto problem whereby one has a non-Afrikan=non-Black parent and in protecting and serving their interests, they sacrifice the interests of the Afrikan=Black race (Williams, 1974, p. 76). Concomitant with this vector is the desire to produce biogenetically compromised “halfricans” and pursuing procreation with non-Afrikans=non-Blacks to this end.

3. The Employment Vector

The employment vector is closely related to the financial vector. It has to do with the compromises that one makes to get and retain employment.

4. The Self-preservation Vector

The self-preservation is linked to violence of various forms in that one is exposed to Afrikans=Black people who are assassinated for staying true to Afrikanness=Blackness. Others who see this precedent have been manipulated into anti-Afrikan=anti-Black positions as a matter of staying alive.

5. The Miseducation Vector

The miseducation vector has to do with the idea “What you do for yourself depends on what you think of yourself. What you think of yourself depends on what you know of yourself. And what you know of yourself depends on what you have been told” (Balola, 2011, p. 13). Miseducation relates to incorrect behavior emanating from false premises engendered by being told the wrong thing.

6. The Ideological Vector

For pale white eurasians, the creation of an ideology is akin to breeding and raising an attack dog. The intended result is for the dog to serve its master, and not for the dog to turn on the one who reared it. This is to say, white ideologies are designed to serve the ultimate goal of pale white eurasians – their continued survival. No matter what the -ism is, it is to serve this function. When Afrikan=Black people adopt white ideologies, the desired outcome, which is almost always achieved, is that either all pale white Eurasians are protected by the hapless victim who imbibes the ideology or at least the progenitor(s) or the ideology are protected in that white-designed -isms are not given to offering a solution to the problem of Afrikan=Black people; namely pale white eurasians and their descendants.

7. The Religious Vector

The religious vector is primarily related to Afrikan=Black people who are compromised by praying to an imaginary white boy on a stick or praying to a rock in the desert five (5) times a day. Other religions work along the same lines in terms of ensuring the deification of eurasian culture and, thereby, ensuring the continued existence of pale white eurasians to the detriment of Afrikan=Black people.

8. The anti-Black identity Vector

The anti-Black identity vector pertains to a sense of self that despises being Black. The idea behind anti-Black identity and its origin is summed up by Baba Ọmọ́wálé:

“Who taught you to hate the texture of your hair? Who taught you to hate the color of your skin? To such extent you bleach, to get like the white man. Who taught you to hate the shape of your nose and the shape of your lips? Who taught you to hate yourself from the top of your head to the soles of your feet? Who taught you to hate your own kind? Who taught you to hate the race that you belong to so much so that you don’t want to be around each other? No… […] you should ask yourself who taught you to hate being what God made you. (Malcolm, 1962)

The singular answer to these questions is that the pale white eurasian teaches Afrikan=Black people all of these things to engender compromise and selling out.

Again, this is an abridged list and these vectors are not mutually exclusive, but rather work in tandem with each other. These are some of the vectors that may be at work in the acceptance of the united snakkkes military base on Afrikan=Black soil.

In the words of illustrious Afrikan=Black historian Nana John Henrik Clarke, “The events which transpired 5,000 years ago; five years ago or five minutes ago, have determined what will happen five minutes from now; five years from now or 5,000 years from now. All history is a current event.” (Fonkeng, 2018, p. 14). In other words, entering into the military base agreement is not a matter of whether or not the united snakkkes will violate the agreement, it is simply a matter of when and in what specific manner.

What about the u.s. and its Self-Appointed Role in Policing the World?

At this juncture, it is important that we debunk the white savior industrial complex narrative in which, in this instance, the united snakkkes comes to save the West Afrikan sub-region from terrorism fomented by either they themselves or their pale white eurasian cousins – the Arabs (Cole, 2012). Again, it behooves us to be cognizant of white eurasian interests such as the role of diamond cartels in the Liberia/Sierra Leone blood-diamond-driven conflicts. It is important to understand French motivations in their so-called anti-terrorism operations in Northern Mali as intrinsically linked to their nuclear energy interests in Northwest Niger.

Further, when one sees these cases, it is imperative that we recognize that there are no gun factories in Liberia or Mali or Niger that are producing the guns or weapons used in these conflicts; rather arms are often exchanged for blood resources. When one analyzes cases like Liberia/Sierra Leone, Mali and Eastern Congo, the u.s. or the white eurasian powers have a vested interest in destabilization in other to get blood diamonds, blood coltan, and blood uranium in these places.

If one does not have this background knowledge, it will be very difficult to understand the actions of the united snakkkes and others and one may think that they are coming because of altruism. The united snakkkes does not act on altruism according to its own words but, more importantly, given its rhetorical ethic, according to its track record of observed behavior.

The thing that separates this agreement from any other agreements is that this agreement is tantamount to a fundamental abdication of sovereignty. When one examines this agreement itself, it talks about things such as the united snakkkes being able to enter and exit the territory and territorial waters of Ghana without any type of consultation. How any well-meaning Ghanaian can hear that without viewing it as an ominous warning is beyond us.

Before we even deal with the united snakkkes violating agreements, we have to look at how one-sided this agreement is from the outset. It says that Ghana cannot inspect any of their vehicles or vessels. They can launch military operations and also once it is understood that this is the home of a united snakkkes military base, anyone who does not get along with the united snakkkes will now have Ghana as a target. We are inviting all of these snakkkes here and we cannot depend on the united snakkkes to honor anything that it says in terms of the so-called defense of Ghana.

It is important to remember that the united snakkkes always acts in its interest, and if it decides that it is not in its interest to ostensibly defend Ghana when the heat is on, Ghana cannot do anything to compel the united snakkkes not to violate the terms of the agreement.

Lack of Reciprocity: Can Ghana set up a Military Base in the united snakkkes?

It should also be understood that there is a fundamental lack of reciprocity in terms of military presence. The united snakkkes of amerikkka claimed all of North amerikkka as its sphere of influence (Jones, 2000). Not only could Ghana not have a base in the united snakkkes proper, but also not in North amerikkka whatsoever. Indeed, the united snakkkes stakes its claim to North amerikkka (and indeed, the entire western hemisphere) as its backyard or sphere of influence as a holdover from colonial times and the wars that followed (Livingstone, 2013).

Conclusion

In conclusion, we would like for people to understand that united snakkkes unilateral “interests” can supersede and/or go against those of Ghana and her people. The united snakkkes always acts unilaterally in its interest, which essentially is all we can expect it to do.

For our part, we must act in the interest of Afrikan=Black people, our children yet unborn. As we have discussed regarding the CWC agreement in which chemical weapons are in the hands of the united snakkkes, what if amerikkkans decide that deploying those weapons within the territory of Ghana is in their interests. Where is the track record of accountability or, phrased differently, who has the will, desire and ability to police the world’s self-appointed police?

Every so often in the midst of the eurasian rhetorical ethic, they actually make statements consistent with their observed behavior such as the idea of “the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must” (Simonen, 2017, p. 125; Thucydides, 431 BCE). This is the idea, which survives in expressions of “might makes right” (Ballou, 1846, p. 119); they tell you “only the strong survive” (Rousseau, 1762, p. 178); they say the survival of the fittest (Darwin, 1869, pp. 91–92; Spencer, 1864, pp. 444-445), etc.

Pale white eurasians routinely invoke their asili to tell you that the archetype of the cave-beast with the biggest stick is the origin of their fundamental worldview. In their treaty-breaking and agreement-flouting, the united snakkkes is being consistent with its asili in the thought that they are stronger than you and you cannot do anything about it.

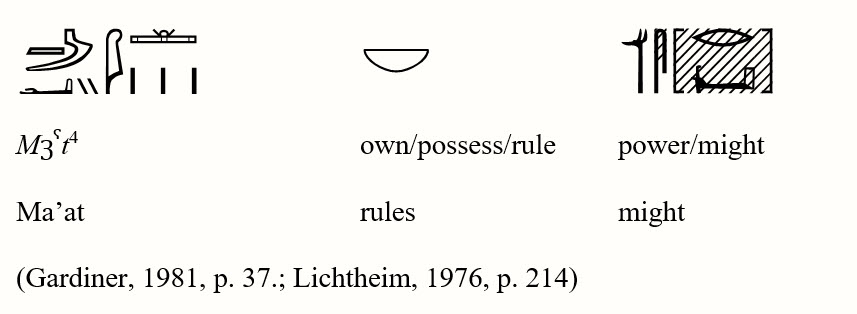

Contrast that worldview with the over 3850-year-old attestation of the fundamentally Afrikan worldview as expressed in Kemet ‘land of Black people’, which states “Do unto another so that he might do likewise” from which other iterations of the so-called golden rule, quite ironically, are plagiarized (Bak, 2016, p. 160).

This Afrikan=Black idea is echoed in the text known as “Horus and Seth” dating to ca. 1149–1145 BCE, which states that Ma’at rules might (Gardiner, 1981, p. 37.; Lichtheim, 1976, p. 214)

This is a starkly different worldview from the snakkke-like worldview of the pale white eurasian. So what happens when a tender woman invites a snakkke into her home? When it bites her, it will simply say “You knew damn well I was a snake before you brought me in.”

References

AFP. (2018, 6 April 2018). Ghana will not offer military base to US: president.

Alexander, H., James, M., & John, J. (1788). The Federalist Papers. Retrieved from http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/fed64.asp

Allotey, G. A. (2018, March 23, 2018). Parliament approves controversial US ‘military base’ deal. Retrieved from http://citifmonline.com/2018/03/23/parliament-approves-controversial-us-military-base-deal/

Ani, M. (1994). Yurugu: An African Centred Critique of European Cultural Thought and Behavior. Trenton, NJ: Africa World Books.

Bak, S. (2016). Smi n Skhty Pn: Multilingual translation of a 4,000-year-old-African story. Popenguine, Senegal: Per Ankh.

Ballou, A. (1846). Christian Non-resistance, in All Its Important Bearings: Illustrated and Defended: J.M. M’Kim.

Balola, L. (2011). The global presence of African civilizations: an interview with Runoko Rashidi. Journal of Pan African Studies, 4(8), 4-15.

Baraka, A. (1978). Reprise of One of A.G.’s Best Poems! boundary 2, 6(2), 327-332. doi:10.2307/302326

BBC. (2018, 20 June 2018). US quits ‘biased’ UN human rights council. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/44537372

Brown, N. (2018, 3 April 2018). The United States is Withdrawing from the International Coffee Agreement. Retrieved from https://dailycoffeenews.com/2018/04/03/the-united-states-is-withdrawing-from-the-international-coffee-agreement/

Brown, O., & Wilson, A. (1968). The Snake. On The Snake. New York: Bell.

Bureau, C. (2018, 05 April 2018). “No US Military Base In Ghana” – President Akufo-Addo.

Cole, T. (2012, 21 March 2012). The White-Savior Industrial Complex. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2012/03/the-white-savior-industrial-complex/254843/

Corrothers, J. D. (1902). The Black Cat Club: Negro Humor & Folk-lore. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

Darwin, C. (1869). The Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life. (5th Edition ed.). London: John Murray.

Deloria Jr, V. (2010). Behind the trail of broken treaties: An Indian declaration of independence: University of Texas Press.

Egan, T. (2000). The Nation-Mending a Trail of Broken Treaties. New York Times.

Feingold, R. (2018, 7 May 2018). Donald Trump can unilaterally withdraw from treaties because Congress abdicated responsibility. Retrieved from https://www.nbcnews.com/think/opinion/donald-trump-can-unilaterally-withdraw-treaties-because-congress-abdicated-responsibility-ncna870866

Fonkeng, E. F. (2018). Words and Worlds of Wisdom: (An African Cosmology). Bamenda, Cameroon: Langaa RPCIG.

Francis, G. H. (1852). Opinions and Policy of the Right Honourable Viscount Palmerston, G.C.B., M.P., &c. as Minister, Diplomatist, and Statesman, During More Than Forty Years of Public Life. London: Colburn.

Franklin, B. (1754, 9 May 1754). Join, or Die. Pennsylvania Gazette.

Gardiner, A. H. (1981). Late-Egyptian Stories (Vol. 1): Édition de la Fondation Égyptologique Reine Élisabeth.

Geggel, L. (2018, 1 June 2017). Trump Pulls US Out of Global Climate Change Pact. Retrieved from https://www.livescience.com/59332-trump-pulls-usa-out-of-paris-agreement.html

Graphic.com.gh. (2018). Ghana-US Military Agreement (FULL VERSION). Retrieved from https://www.graphic.com.gh/news/general-news/ghana-us-military-agreement-full-version.html

HarperCollins. (2018). military base. Retrieved from https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/military-base

Heer, J. (2016). Is Donald Trump the fabled Snake? Retrieved from https://newrepublic.com/minutes/138103/donald-trump-fabled-snake

Hilliard, A. G., Williams, L., & Damali, N. (1995). The Teachings of Ptahhotep: The Oldest Book in the World. Grand Forks, ND: Blackwood Press.

Hord, F. L., & Lee, J. S. (1995). I Am Because We are: Readings in Black Philosophy. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press.

James, J. (1972). Discrimination in Employment (Oversight Hearings).

Jefferson, T. (1801). Jefferson’s First Inaugural Address, March 4, 1801. Retrieved from https://www.history.org/Media/flash/Jefferson/reportongov.htm

Jones, M. (2000). America’s backyard. Diplomacy & Statecraft, 11(1), 291-298. doi:10.1080/09592290008406150

Kambon, O., & Yɛboah, R. M. (2018). Haiti, Morocco and the AU: A Case Study on Black Pan-Africanism vs. anti-Black continentalism. CODESRIA: Identity, Culture, And Politics 19(1-2), 41-64. Retrieved from https://www.codesria.org/spip.php?article3039&lang=en

Koplow, D. A. (2013). Indisputable Violations: What Happens When the United States Unambiguously Breaches a Treaty. Fletcher F. World Aff., 37, 53.

Lichtheim, M. (1976). Ancient Egyptian Literature: A Book of Readings: The New Kingdom (Vol. 2). Oakland: University of California.

Livingstone, G. (2013). America’s Backyard: The United States and Latin America from the Monroe Doctrine to the War on Terror. Location: Zed Books.

Malcolm, X. (1962). Who Taught You to Hate Yourself?

Moore, L. F., Gray-Garcia, L. T., & Thrower, E. H. (2016). Black & blue: policing disability & poverty beyond Occupy. In Occupying disability: Critical approaches to community, justice, and decolonizing disability (pp. 295-318). New York: Springer.

Otto, S. (2007, 29 September 2007). Some organizations still support Pol Pot. Retrieved from https://polpot8.blogspot.com/2007/09/

Press, C. U. (2018). Base (Military). Retrieved from https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/military-base

Roget, S. (2018). Why Is The US Allowed To Have Military Bases All Over The World? Retrieved from https://www.ranker.com/list/how-america-has-military-bases-all-around-the-world/stephanroget

Rousseau, J.-J. (1762). Social Contact in Social Contract and Discourses, trans. GDH Cole (New York: EP Dutton, 1950), 34.

Shuffield, R. (Writer). (2006). Thomas Sankara: the upright man. In Z. Production (Producer). France: California Newsreel.

Simonen, K. (2017). The Strong Do What They Can and the Weak Suffer What They Must—But Must They? Fairness as a Prerequisite for Successful Negotiation (Benchmarking the Iran Nuclear Negotiations). Journal of Conflict and Security Law, 22(1), 125-145.

Spencer, H. (1864). The Principles of Biology: William and Norgate.

St Pierre, M. W. (2014). Preventing China s Rise: Maintaining United States Hegemony in the Face of a Rising China. Retrieved from https://apps.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a614147.pdf

Staff, J. C. o. (2018). DOD Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms. Retrieved from http://www.jcs.mil/Doctrine/D/

TeaandCoffee.com. (2018, 3 April 2018). US Withdraws from the International Coffee Agreement. Retrieved from https://www.teaandcoffee.net/19547/news/us-withdraws-from-the-international-coffee-agreement/

Thucydides. (431 BCE). History Of The Peloponnesian War: Sixteenth Year of the War – The Melian Conference – Fate of Melos. Web: mtholyoke.edu.

Toensing, G. (2013). Honor the Treaties’: UN Human Rights Chief’s message. In: Retrieved.

Trump, D. J. (2012, 19 November 2012). It’s my nature. Retrieved from https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/270563974527995905

Wang, H. L. (2015, January 18, 2015). Broken Promises On Display At Native American Treaties Exhibit. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2015/01/18/368559990/broken-promises-on-display-at-native-american-treaties-exhibit

Washington, G. (1796). Farewell Address, 1796. Avalon Project at Yale Law School.

Williams, C. (1974). The Destruction of African Civilization. In. Chicago: Third World Press.

Wilson, D. A. (1992). Blueprint for Black Power Lecture [Press release]. Retrieved from https://blackaccessnetwork.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/blueprint-for-blackpower-lecture-by-dr-amos-wilson.pdf

X, Malcolm. (1963). Message to the Grassroots. Retrieved from http://www.csun.edu/~hcpas003/grassroots.html

Authors

Author 1: Ọbádélé Kambon

affiliation: University of Ghana

mailing address: PO Box LG 1159, Legon, Accra, Ghana

email address: [email protected]

Author 2: Nana Yaw Mireku Yɛboah

affiliation: University of Ghana

mailing address: LECIAD, University of Ghana, Legon, Accra, Ghana

email address: [email protected]

Ọbádélé Kambon completed his PhD in Linguistics at the University of Ghana in 2012, winning the prestigious Vice-Chancellor’s award for the Best PhD Thesis in the Humanities. He also won the 2016 Provost’s Publication Award for best article in the College of Humanities. In 2019 he was the recipient of the [Nana] Marcus Mosiah Garvey Foundation award for excellence in Afrikan Studies and Education. He is a Senior Research Fellow and Head of the Language, Literature and Drama Section of the Institute of African Studies at the University of Ghana. Okunini Kambon is currently Editor-in-Chief of the Ghana Journal of Linguistics as well as Secretary of the African Studies Association of Africa. His research interests include Serial Verb Construction Nominalization, Historical Linguistics, Kemetology, & Afrikan=Black Liberation.

Roland Mireku Yeboah is a PhD Candidate in International Affairs at the Legon Centre for International Affairs and Diplomacy (LECIAD), University of Ghana. He is a product of the Institute of African Studies, and LECIAD both at UG, where he obtained MPhil in African Studies (history and politics) and MA in International Affairs respectively. His research interests include Africa’s international relations, global Black struggle of the 21st century, and secessionist conflicts in Africa. His publications have appeared in the Journal of Black Studies, Journal of Pan-African Studies and the Legon Journal of International Affairs. He can be contacted at [email protected] or +233 0570857119