TTT on Occupy, Dec. 2011

PART’s Perspective: Occupation, Liberation, and Overcoming Contradictions Among the 99%

by Michael Novick, Anti-Racist Action-Los Angeles/People Against Racist Terror (ARA-LA/PART)

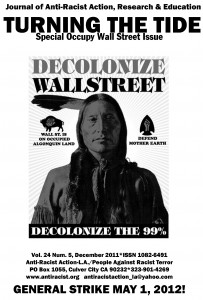

Somewhat akin to the occupation of Alcatraz Island more than four decades ago, Occupy Wall Street has stood the concept of “occupation” on its head. Groups on the left that were chanting “Money for jobs and education, not for war and occupation” have had to change the last word to “corporations.”

The occupation of Alcatraz, however, was a clearly anti-colonial insurgency that helped spark the on-going struggle for indigenous sovereignty and self-determination that continues to this day and has reached global proportions. The Alcatraz occupation liberated both the shell of an imperial prison and the conquered and colonized land on which it was built. It occurred within a countrywide and worldwide upsurge of colonized and oppressed people and of a new generation claiming its place in the world. Though there are both generational and global parallels today, Occupy Wall Street distinguishes itself from the Alcatraz occupation in having neither explicitly anti-colonial nor categorically anti-capitalist politics.

Just a few short months ago, the editorial in Turning the Tide sought to understand the remarkable political quiescence in the US when the rest of the world was on fire. We analyzed the psychosocial breaks with the Empire that needed to occur to unleash the righteous anger and resistance of people in this country, particularly those of European descent. Immediately and unexpectedly, like Marx’s “old mole” of revolution, the Occupy movement burst upon the scene to galvanize a broad sector of society.

It has ignited hopes of a rebirth of direct action and militant resistance, and spread back around the world as a beacon to some of the very struggles that inspired it. Yet ironically, dissent, resistance and direct action have spread like wildfire even as the consciousness and ideology of the Occupiers have yet to show signs of a thorough and fundamental break from the identification with the oppressor that has long held such resistance back. This is a measure of not only the grip of Empire and settler colonialism on US psyches, but also the depth of the economic crisis and contradictions in which that empire is ensnared. These are beginning to fray the ties that bind people in the US to our own oppressors no matter people’s consciousness.

The question for all Occupiers, all attracted to and inspired by the Occupy movement, and especially for those who are revolutionary-minded, is how to overcome that contradiction between consciousness and practice.

How can we not only sustain, but also build and advance the Occupy movement? How can we birth the methods, organizational forms, and strategies that will advance the Occupy movement, without killing the goose of horizontal inclusiveness – the 99% — that has laid the golden egg of movement?

As always, a process of constructive criticism and self[1]criticism is necessary to identify strengths and overcome weaknesses. Studying not only its own brief history but also the rich historical record of previous errors and failures can best enable us to chart a path forward to Occupy 2.0. This applies the open source approach, of users collaboratively reshaping and recreating their tools and making them more usable, useful, and user-friendly through practice, the shared experience of bugs and glitches, and the discovery of new desirable features. At Occupy LA, it often seems that name-calling and email flame wars have been far more common than constructive criticism and self-criticism, so beginning to apply those methods will be a step forward in itself.

The bulk of this issue is dedicated to theme of decolonization, as has the bulk of the work and analysis of ARA-LA/PART over more than two decades. But understanding that many drawn into political activity by the Occupy movement may be reading this alone, or seeing TTT for the first time, I want to underscore the fundamental basis of that approach. You cannot understand, let alone transform, US society unless you grasp that it is an Empire — a state, an economy and a social formation based on settler colonialism, land theft, genocide, and chattel slavery. These on-going realities have shaped and continue to shape class formation, national identity, and the nature of even dissident and oppositional struggles.

The Occupy movement is a case in point. First, Occupy bases itself on the goal or tactic of reappropriating the commons, countering the privatization and corporatization of public space. But there is a fundamental difference that must be acknowledged about the commons in the U.S. compared to most other societies. The commons in the US context is not the remnant of an earlier, land-based socio[1]economic formation like European feudalism or African communalism. It was created through acts of war, conquest and “ethnic cleansing” – the physical and cultural genocide of an indigenous population. Failing to recognize this makes Occupy complicit in this matrix and incapable of surmounting its contradictions.

Second, Occupy bases itself on the kind of rudimentary class-consciousness of income and wealth that has always been a hallmark of US settler colonialism. Applying the paradigm of the 99% on a global level would quickly illustrate the flimsiness of this thinking. The global 99% are almost entirely outside the United States with the exception of some sections of the urban and rural poor, of indigenous and other internally colonized people, the “Third World” that exists inside the “homeland” of the Empire. The World Institute for Development Economics Research reports that in 2000, the richest 1% of adults owned 40% of global assets. The richest 10% accounted for 85% of the world total, while the bottom half of the world adult population owned 1% of global wealth.

A person in the US at the average income level of the bottom 10% of the US is better off economically than 2/3 of the world’s population. On a global level, $2161 puts you into the top half f the world wealth distribution, and $61,000 puts you into the top 10%. These global realities are the reason the notion of a “middle class,” and the call for “middle class jobs,” is so deeply embedded among even working class people in the US and within the Occupy movement.

But these realities are changing, and the change is what accounts for the appeal of Occupy. Globalization and the “third-world-ization” of the US have meant that many people are xperiencing the realities or the prospects of a permanent class fall. Class contradictions are inexorably reasserting themselves through a process of national “convergence” between rich and poor nations. More important, though per capita incomes of nations may rise, the lion’s share of growth is absorbed by an international elite (still primarily and ostentatiously concentrated in the US and Europe, but including also Japan, parts of China, India and Indonesia, Israel and Arab elites, and Brazil).

Correspondingly, growing sectors of the population in advanced industrial and settler colonial societies are experiencing losses even as the US continues to possess 25% of the world’s wealth (no other country reaches the 5% level of concentration).

For some, this has meant belt-tightening, foreclosure and a first experience of protracted unemployment. In that sense, Occupy is a response to conditions and frustrations similar to those addressed by the Tea Party. But fortunately, Occupy has had a more spontaneous emergence than the Tea Party’s astro-turf launch by the 1%, and it gains from its understanding of that phenomenon, as well as its intention to avoid being ensnared by the Democratic Party as the Tea Party was by the Republicans. Also, the Occupy movement’s social base embraces organized and unorganized labor and other lower social strata. Because for others within the US, globalization means the deepening and extension of the conditions of homelessness, incarceration, malnutrition, and early death that illustrate the reality that some of the global 99% do in fact reside inside “the richest country in the world.”

The Occupy movement is a cross-class movement despite its assertion that the 99% constitute a single social entity. Obscuring or denying class and colonial contradictions does not eliminate them; it makes them fester. Casting Occupy’s demands or objectives within the appealing[1]on-the-surface proposition that “the richest country in the world” shouldn’t allow foreclosures, or failing schools, or homelessness, is a recipe for failure. At a teach-in at Occupy Los Angeles, Robert Reich proclaimed that this struggle was not class war, and that the goal of the Occupy movement was to “save capitalism from itself.” This call to save a system that is beyond repair or redemption, and whose further extension could well doom humanity and the biosphere, was greeted with silence (even from a crowd of listeners who were far older, whiter and better off than the Occupiers). Yet many in the Occupy movement want to limit its program to re-regulation of banks, taking money out of politics and ending corporate personhood.

The emphasis on the concentration of wealth and income inequality is a mixed bag. How much concentration in how few hands is “acceptable”? Would 20% of national wealth be big enough to satisfy the 1% and small enough to quiet the concerns of the 99%? To ask the question is to recognize that such demands amount to asking, in the words of Malcolm X, someone who has stabbed you in the back to pull the blade back out a few inches. The same can be said about some of the demands for democratization. Though Occupy responded angrily to the Military Authorization Bill that allows indefinite military detention of US citizens without trial, neither Occupy nor the Democrats seem to be talking any more about repealing the USA PATRIOT Act, closing Guantanamo or abolishing Homeland Security. Within Occupy LA (finally mostly disabused by reality) there was strong sentiment that “the police are part of the 99%.” Reality has taught that they are the enforcers of the rule of the 1%.

Occupy must begin to put forward not demands (which presupposes they will be granted by those in power) but objectives – declarations of the kind of world we want and will build to replace a system that is rotten to the core. Economic objectives would include developing an ethical, environmentally sustainable, democratic economic system that serves to meet human needs and heal the environmental and social damage that the current system has caused. This would be a system that honors human dignity, labor and creativity, and that ensures first that all are well-fed, well-clothed and well[1]housed, with clean water, and that other human needs, such as education and health care, are met before any enjoy champagne and caviar. No amount of tinkering or reform could turn capitalism or colonialism into such a system.

Occupy LA has issued a call which is step in such a direction, to “Occupy the Ports” on Dec. 12. This is part of a day of action, march and boycott for migrant rights, full legalization and good jobs for all, and the beginning of a process of building towards a General Strike on May 1. That initiative is spreading with a call from Occupy Oakland to shut down the West Coast ports, and a General Strike call from Occupy DC.

Learn more about this from [email protected] and at www.occupytheports.com.

This begins to chart a path forward based on direct action, base-building and alliance building, engaging with other social forces seeking to transform this society – not from ‘within’, but rom below. This will also help Occupiers and the movement as a whole to resist the schemes and seductions that seek to ensnare Occupy within electoral politics and in particular the Democratic Party, which has been the graveyard of transformational and liberating social movements for generations.

Hopefully, the Occupy movement will become a pole of attraction that will instead pull labor, anti-war, environmental and other such movements out of their orbital path into the black hole of the Democrats before they pass the event horizon from which no light emerges.

It can do so if Occupy aligns itself with the wretched of the earth, the most oppressed and exploited, the prisoners and ex-cons, the homeless, unemployed and welfare recipients, the indigenous, the anti-colonial, anti-capitalist struggles not only globally, but within the US itself.