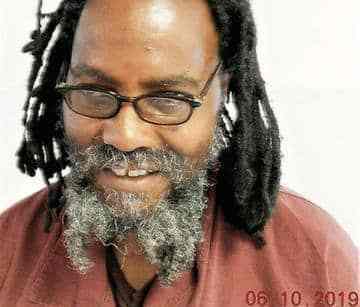

Mumia Abu Jamal Embraces LGBTQ Liberation

https://www.prisonradio.org/commentary/mumia-embraces-lgbtq-liberation-on-99-5-fm-wbai/

excerpts from an interview by Out-FM

(This interview with Mumia by Bob Lederer and the associated documentary also ran in full on KPFK’s Somethings Happening program, as well as in a later one-hour edited version. The full transcript with extensive historical background material is available on the Prison Radio website, and the audio is there as well as archived at wbai.org, kpfk.org, and outfm.org)

BOB: Brother Mumia, thanks so much for agreeing to this interview for Out-FM. It’s an honor to have this opportunity to speak with you, as you are a brilliant and empathic revolutionary analyst, and a role model for progressive journalists and for all people working for peace and justice. This is especially fitting as we celebrate the 100th birthday of the Black gay literary genius and Black liberation fighter James Baldwin.

MUMIA: Well put. You actually remind me that this morning, when I was walking in the yard, NPR did a piece on precisely that – James Baldwin’s 100th centennial of his birth…. The guest on NPR opened up a bookstore called Baldwin & Company, and the thing has lines around the block, and he’s getting orders every day. He said the most recent was from China, reading Baldwin stuff. So you know, as a writer, as a revolutionary, as a thinker and an organizer, it cannot be more praiseworthy for a writer to continue to have impact a century after his birth.

BOB: Brother Mumia, I want to turn now to your evolving views over the decades on the role of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people in U.S. society. You have indeed shown a remarkable evolution, as have many in the overall society, in parallel with the growing organizing and strength of the diverse LGBTQ+ movements demanding our human rights.

In a 2012 book, [you wrote:] “…Huey P. Newton spoke out, back in 1970, about gay liberation. He didn’t just mention it. He said…‘We, the Black Panther Party, support gay liberation just as we support women’s liberation.’ He saw it as part of the struggle for human liberation.…It was the most forward position of any radical and revolutionary movement of the period, and reflected Huey’s keen thinking on issues before his time. So even in a movement perceived as ‘masculinist,’ there were these insights.” And I would add one direct quote from Huey Newton’s statement, which listeners can read in full at outfm.org. He wrote: “The terms ‘faggot’ and ‘punk’ should be deleted from our vocabulary, and especially we should not attach names normally designed for homosexuals to men who are enemies of the people, such as Nixon or Mitchell [who was the Attorney General]. Homosexuals are not enemies of the people.” And that’s Huey Newton in 1970.

So Mumia, as you look back at your [own] July 1970 statement in The Black Panther calling racist Philadelphia police officials “faggots” who engaged in “perversion,” and then look at Huey Newton’s August 1970 letter – just a month later – supporting the women’s liberation and gay liberation movements, can you tell us more about your viewpoint at that time, when you were 16, and more about how other straight men, as well as women, in the Party viewed the letter, and what impact it had?

MUMIA: Well, if you’re talking about my letter, I actually don’t have a memory of it, because this is like my 70th year of life. You’re talking about my 16th year of life. But when I read your note referring to that, my mind actually flashed to the Minister of Information at that time, Eldridge Cleaver, who wrote and spoke in similar ways. And as the lieutenant of information of the Philadelphia branch, and later at the national office and newspaper and someone working on the paper, I really adored Eldridge. He was very influential in my thinking, and so I was probably consciously imitating Eldridge and imitating his speech. When you think about what Huey said at the Revolutionary People’s Constitutional Convention about gay folks and lesbian and queer folk, I must be honest with you: It was not well received by members of the Party. We were shocked in some ways, confused in other ways. But as usual, this was Huey at his finest, and he was a true revolutionary intellectual who was usually ahead of his peers. And they were, let’s be honest, there were few peers of Huey Newton, which is a good thing and a bad thing, in a way. But what Huey was beginning to understand, I think, especially coming from his prison experience, is that any revolution, any real struggle, in the bastion of the Empire had to really involve all kinds of people in that struggle to be successful. Now to understand that intellectually is one thing, but to understand it empathically, right?, is another. But Huey was always ahead of the pack. That was just the nature of his really acute intelligence and his perception. But you know, 16 is not 70.

BOB: Mumia, in terms of the 1970 Panther-led Revolutionary People’s Constitutional Convention, which you mentioned a minute ago, can you talk about the two sides of this historic coin: 1) the leadership of the Black Panther Party in gathering such diverse movements to grapple with a reimagined United States and 2) the failure of that process to advance – in particular, the role of white supremacy within the Left, then and now?

MUMIA: You sound like you read my book, We Want Freedom: A Life in the Black Panther Party.

BOB: I have.

MUMIA: I should have known! I was remarking earlier about how Huey was really ahead of the times. In retrospect, when I think about it, and I think about the many positions that the Party had, the Party was ahead of its times. And sometimes, when you’re in that structure and you make a call, you expect people to respond to the call, or sometimes some people aren’t ready for the call that you’re making. So that you know you need to develop it further and even explain things.

I mean, think about this: In 1966, October 15th, the Party began with Huey P. Newton and Bobby G. Seale, two college students who were reading stuff, who were reading primarily The Wretched of the Earth by Franz Fanon, which deeply influenced how we saw the world. But this Party really grew by leaps and bounds, so that two or three years later it had 44 chapters and branches all across the United States and some offices overseas, right? And we’re talking to – by intention – ghetto folks who we called the lumpen, but people who had difficulty reading stuff about other countries, ideas that – This call is from a Pennsylvania State Correctional Institution, Mahanoy, this call is subject to data monitoring – ideas that were coming from other parts of the world because we were involved in really a world revolution. It was natural for us. But that doesn’t mean it was natural for people that we were speaking to or writing to.

And to the Party’s credit, some branches organized really community schools, right? Or areas where members could really, you know, sit down and rap with people and answer questions and explain things. All chapters didn’t have that, though they had it for members but they didn’t have it for the community. Some chapters weren’t big enough. Some chapters weren’t sophisticated enough. But I mean, that’s your most important work, right? Your most important work isn’t selling newspapers, even though that’s important by putting out information via the newspaper, but your most important work is really communicating with people, answering their questions, letting them know how you see the world, and then bringing them into that construct. That didn’t happen in many ways, because we were so far advanced. The RPCC could have been a different kind of thing, if we had projected out to our various audiences that this is the work of the RPCC or the Revolutionary People’s Communications Committee and Network, instead of kind of springing it on people when they gathered at Temple University. So, I mean – This call is from a Pennsylvania State Correctional Institution, Mahanoy, this call is subject to data monitoring – think long and hard about how to organize, how to talk to people and listen to people, because you know, they have their ideas as well!

BOB: Mumia, I want to ask you about your conclusions about the roles of both women and sexism in the Black Panther Party and the broader Black liberation movement. Can you share your assessment of the Party’s gender relationships in the context of a patriarchal society, and what you learned from the women whom you met while in the Party and then recontacted in writing your book We Want Freedom? Can you also comment on the little-remembered FBI-directed repression faced by Panther women, and their brilliance in DEFEATING frame-ups, like Afeni Shakur and Ericka Huggins. Incidentally, Ericka is now a self-identified queer woman and a wonderful community activist, change-maker, and healer in Oakland whom we’ve interviewed several times on Out-FM.

MUMIA: Well, I’ve spoken about it. I don’t know if I say that in We Want Freedom, but I hear a lot of comments about the chapter I wrote about women. The women really were the glory of the Party. And I mean, they were the Party’s hardest workers, the most disciplined members and leaders. And you know, a lot of times when a brother would go around the corner, and even though it’s against orders, as he would smoke a joint or have a drink, the sisters were there early every morning to open the office or to open the Free Breakfast Program and make sure that the people got served first. They were the first to open and the last to leave. They were the glory of the Party.

And you talk about Afeni. I quoted from her closing argument to the jury in the Panther 21 trial. It’s difficult, even all of these years later, for me to read that without weeping, because she was brilliant. She was the best lawyer, because she understood how to talk to people and to reach them and to, you know, unwrap their fear and to open their hearts. And that was hard work back then. She did it effortlessly. She was brilliant.

And, you know, Ericka: Most people knew of Ericka by reading her poems, right? Her poems just touch the heart and move people in ways that a hard, didactic, analytical, theoretical article could not. She knew how to reach people right, and especially with the tragedy of the loss of her husband, John.

The sisters were the glory of the Party, and in many ways, they remained so even after they left the Party, because they still organized in the community. They still – I mean, there’s no Black Panther Party formally right now, but they do the work that they were trained to do when they were young sisters, and they’re still active in the world, explaining changes in the world, helping the community cope with its many, many challenges. And they were glorious. They were and are glorious sisters.

BOB: Mumia, can you reflect back on your views – now I’m asking you about 33 years ago – in 1991 when you told QUISP [Queers United in Support of Political Prisoners] about your belief that “heterosexual hookups” were the only natural ones? So three questions about that:

a. What was the basis of your views at the time?

b. How have your views evolved in the 33 years since then, and who and what influenced your evolution?

c. Where do you situate the liberation of queers and trans people in the larger context of human liberation?

MUMIA: When I was writing to QUISP, I was writing from the perspective of a MOVE supporter and someone who was following the teachings of John Africa, and really what was a naturalist revolutionary movement, as opposed to a nationalist one. But what we learned, right, when we study revolution, is that all things change, and that means perceptions, it means perspectives, it means even vision. Like, you know, we see and experience things differently.

One of the things that I don’t believe you have read, even though you’ve done extensive research of course, is one of the last statements of Delbert Africa. I believe I put it in a commentary that I did, shortly before he came out of prison. And this is like, you know, one of the elder brothers of the movement, one of the really clearest thinkers, best speakers and best known of MOVE people, and he made a clarion call to LGBT people. It surprised me to read that, but he was doing that in the context of what? [With] the Black Lives Matter movement that was surging several years ago, we began to understand that the leaders of that movement tended to be gay men and lesbian women. And they were doing some real hellified organizing about the matter of Black life under the threat of police terror. And we hadn’t seen any kind of organizing like that in years, in decades. So, you give credit where credit is due, and they were due, and they continue to be due, tremendous credit for their organizing around the simple principle of black life, and it took courage –

At that point, the prison phone system automatically cut off at the 15-minute limit. Fortunately, Mumia was able to call back later.

BOB: Finally, Mumia, I’d like to ask you about homophobia and transphobia within the prisons where you’ve been held, both from the staff and the other incarcerated men. Can you share any observations or conversations you’ve had over your 42 years in prison with gay men or trans women that have nourished your understanding of what they’re subjected to and their overall situation in prison?

MUMIA: Well, you know, being in many ways, a blockhead and a nerd, I used to think that for a gay or even a trans man in prison would be a touch of heaven. It’s quite the reverse. They catch hell from prisoners and staff alike. So think about the alienation in isolation that breathes in such a person. I’ve seen people – literally seen them – try to commit suicide by jumping off of a rail onto the floor. If you hit your head or your neck, you can kill yourself, and I’ve seen that several times, in several places, in several prisons. Prison, by its nature, breeds isolation in human beings and atomizes them to the extent that it further isolates and separates them. And for trans and gay men in prison, it’s a hell in a hell, you know? They get the worst of it.

And I think the only people who really get worse – the worst treatment in prison – are jailhouse lawyers, because they tend to challenge the system and try to transform how prisons function. But it’s not a good place. It can never be a good place. It’s not designed to be a good place, and everything about it really works through the destruction of human and social relationships.

BOB: Wow. Any last words as we wrap up?

MUMIA: I want to thank you for your long support and your correspondence, and I applaud you as well.

BOB: Thank you so much. Be well, and let’s free Mumia right away!

MUMIA: Thank you, thank you.

Again, I’m Bob Lederer and you’ve been listening to my recent phone interview with political prisoner Mumia Abu-Jamal. In recent years, Mumia has become increasingly outspoken about queer and trans issues. In 2000, he wrote an insightful and moving commentary denouncing the brutal murders of three white gay men: Matthew Shepard in Wyoming in 1998, Billy Jack Gaither in Alabama and Eddie Northington in Virginia, both in 1999. He was responding to an LGBT campaign in support of his freedom called Rainbow Flags for Mumia. It’s available in Mumia’s recent reading of it here: https://www.prisonradio.org/commentary/a-letter-to-workers-world-newspaper/