Where Are the Voices of Women Prisoners?

By Uhuru Rowe

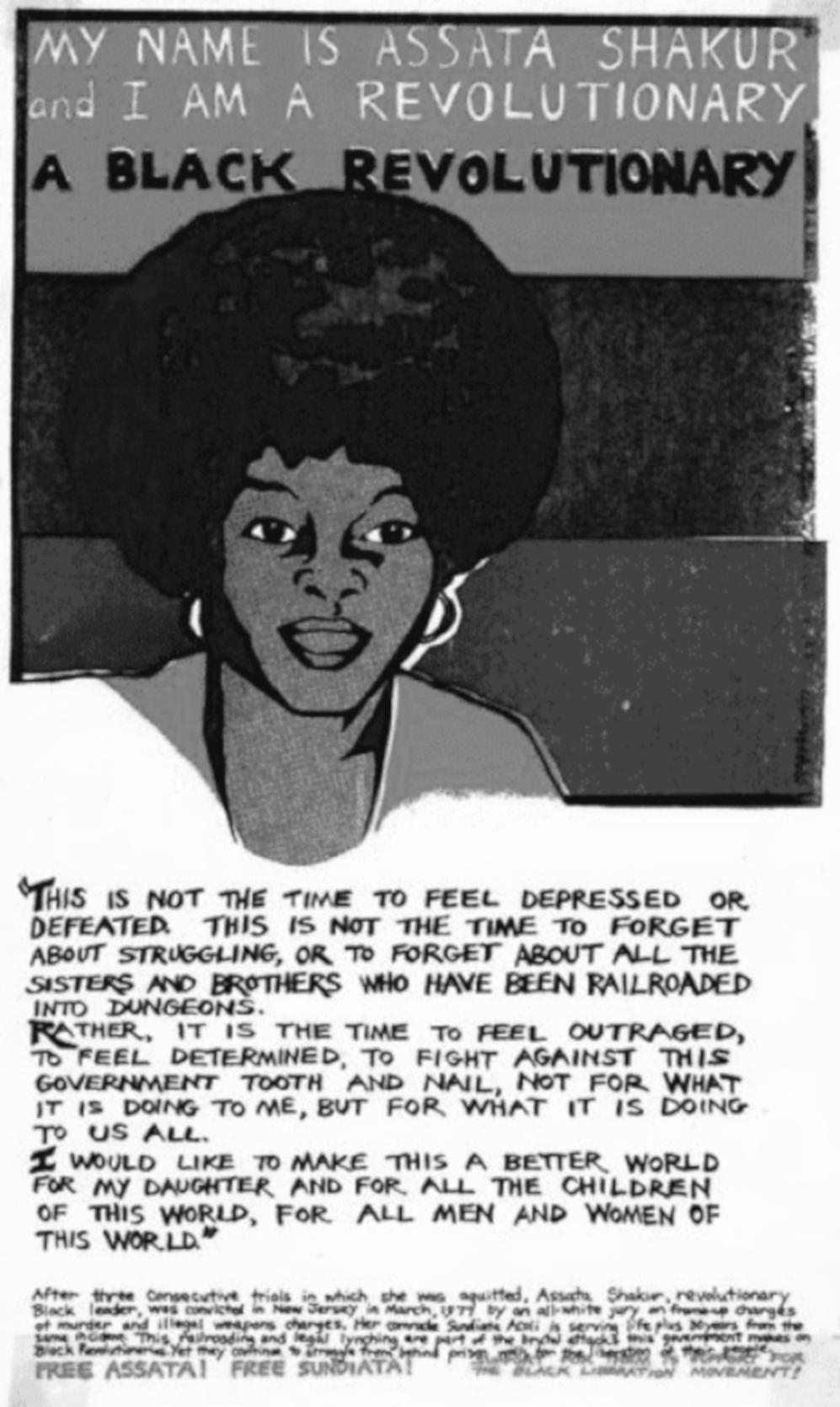

Though it is often not widely known, or perhaps ignored altogether, since the very first act of violence committed by European enslavers against Black people, Black women have played a major role in Black militant resistance against slavery, colonialism, racial violence, and patriarchal white supremacy. Consequently, they have suffered just as much state repression and abuse and torture in jails and prisons as their male counterparts. Assata’s history is a testimony to this fact.

Assata was born on July 16, 1947, and spent the majority of her young life in Wilmington, North Carolina, where her grandmother — more than anybody else — taught her the importance of having a voice, speaking up against racial and gender oppression, and demanding respect, especially from racist white people in the segregated South. When she was in the third grade, Assata and her family moved to Queens, New York, where she eventually quit school, flirted with sex work, worked at odd jobs, but eventually went back to school, graduated, and then went to Manhattan Community College, where she became politically active.

It was in college where she began checking out various political organizations like the Republic of New Afrika and the Black Panther Party.

Assata said her first contact with the Panthers was through Zayd Shaqur, a Panther leader from the Bronx, and other Panthers who were invited to Manhattan Community College to give lectures. She would later join the prestigious Harlem chapter of BPP after visiting the Black Panther headquarters in Oakland, California.

It wasn’t too long after that when Assata and the BPP in particular, and the Black Liberation Movement in general, became the number one target of J. Edgar Hoover’s illegal and secretive counterintelligence program, also known as COINTELPRO. As a result, Dr. Huey P. Newton, the Party’s Minister of Defense, was framed for the killing of an Oakland police officer and imprisoned on October 28, 1967. Lil Bobby Hutton, the party’s first member and first treasurer, was murdered by Oakland police on April 6, 1968. Lil Bobby was the first, but not last, member to be assassinated by police. Bunchy Carter and John Huggins, two Panther leaders in Los Angeles, were murdered on January 17, 1969, during a COINTELPRO instigated beef between the LA Panthers and Ron Karenga’s United Slaves Organization. Twenty-one Black Panthers were arrested or indicted in New York on April 2, 1969. Fred Hampton and Mark Clark, two Panther leaders in Chicago, were assassinated by Chicago police on December 4, 1969. And then the infamous confrontation with police on the New Jersey Turnpike on November 2, 1973 that left Zayd Shakur dead, and both Sundiata Acoli and a wounded Assata jailed and sentenced each to life plus thirty years in prison.

After her arrest, Assata learned first-hand about the horrors of prisons. Of course she was aware of the state-sanctioned racial violence against Black people in society, but she also came to see that what Black people in prison experience was an extension or continuation of that racial violence.

For instance, in the very first chapter of her autobiography, Assata talks about how she was constantly beaten, harassed, and tortured by the police and received little to no medical care for her gunshot wound. She detailed in other chapters how she was transferred from prison to prison, even to a federal prison in West Virginia.

Those of us in prison call this repressive tactic Diesel therapy and it is still used today against politically active prisoners to keep them disoriented and far away from their base of outside support.

Assata detailed in her essay “Women in Prison,” published in the Black Scholar in 1978, that the majority of women at Rikers Island Jail were Black and Puerto Rican, and that most of them were mothers and were mostly jailed for sex work and drug-related cases. She also mentioned that other women were there for stealing and hustling — crimes of survival committed, not only to ensure their survival, but the survival of their children because of the lack of employment and inadequate welfare assistance. https://portside.org/2015-06-10/assata-shakur-women-prison-rikers-island-70s

These conditions still exist. For instance, a pamphlet I received from the California Coalition for Women Prisoners states that the population of women in prison in the US has grown by 800% since 1980. Over 80% of people in women’s prisons there are serving time for actions that are property and drug related. Approximately 70% of people in women’s prisons are mothers, and the majority were the primary caretakers of their children before they were sent to prison. Approximately 80% of women in prison have experienced abuse even as children and adults.

These national statistics reflect what is happening here in Virginia. The Vera Justice Institute reports that the number of women in Virginia’s prisons has increased more than tenfold, from 307 in 1978 to 3,154 in 2017, and the number of women in Virginia’s jails increased more than nineteenfold, from 216 in 1970 to 4,150 in 2015.

These statistics reflect that women and girls are increasingly being targeted by the carceral state, and reports show that conditions have gotten worse for people in women’s prisons since Assata wrote her essay. One of those reports is a 2022 Associated Press investigatory report detailing numerous rapes of incarcerated women at the Federal Correctional Institution in Dublin, California, which is nicknamed the “Rape Club” by both incarcerated women and prison employees. The perpetrators of these rapes range from a warden all the way down to a chaplain and maintenance worker.

Another Associated Press report from 2021 detailed how 150 staffers at the Sununu Youth Services Center — formerly the Youth Services Center — in New Hampshire, beat, raped, and gang-raped more than 200 children, including girls, from 1963 to 2018.

With this knowledge, the question is, what can be done? Assata says in her essay “Women in Prison” that about 8% of the women engaged in some form of lesbian relationship, that there was no connection between lesbianism in prison and the larger Women’s Movement, and that the Women’s Liberation Movement and the Queer Liberation Movement were disconnected from the women at Rikers. I submit that this disconnect was not due to the women’s lack of interest in the broader liberation movements. In fact, I submit that it was the other way around — that it was those movements that were uninterested in educating, politicizing, and organizing the women at Rikers. After all, Assata did say in her essay that there was no revolutionary literature laying around.

This is reflected in the current times by most prison justice and abolitionist organizations catering to and centering the voices and plights of incarcerated cis men while consciously and/or unconsciously overlooking or completely disregarding the voices and plights of incarcerated women, especially incarcerated trans women.

As an example, I receive a total of five radical and abolitionist newsletters and newspapers which frequently publish articles written by or about incarcerated people in regards to the conditions in prisons, and during the last year, none of them contained an article by or about an incarcerated queer or trans person, and only one of them — the San Francisco Bay View — contained an article written by an incarcerated woman. Is this due to a lack of incarcerated women and queer and trans people’s unwillingness to write about conditions in prison? Is this due to sexism, queer- and transphobia, in many prison justice/abolitionist movements? Or is it because an incarcerated trans woman filing a lawsuit to force prison officials to give her a sex reassignment surgery, or incarcerated women collectively refusing to lock down in their cells until their demands for more tampons are met, is rendered invisible because these actions are feminized, queerized, and not considered real resistance behind these prison walls?

Women and LGBTQ+ people are not only the fastest growing populations in prisons, but they are also the most oppressed group inside the sprawling prison-industrial complex. Their special oppression should give them a vanguard role in the anti-prison movement. In her essay, Assata said, “Black women can never be free while Black men are oppressed.” In the same vein, the modern prison justice/abolition movement will never be successful until incarcerated women and LGBTQ+ people are sought out, accepted, embraced, and included as part of the vanguard movement to shut down and abolish these prisons, jails, and detention centers, and the carceral state as a whole. All power to ALL the people!

Read more from and about Uhuru B. Rowe, a conscious prisoner, here:

https://consciousprisoner.wordpress.com/

https://www.instagram.com/p/CY6x-D4gVVM/

justiceforuhururowe We are thrilled to announce that Uhuru’s sentence has been (partially) commuted!

Thanks to Uhuru’s determination, the work of the members of the Justice for Uhuru Coordinating Committee, and the support of all of you, Uhuru Rowe’s 93-year sentence was commuted by Governor Northam before he left office. Uhuru will now be released from prison October 18th, 2025, as opposed to his previous release date of 2076. Uhuru will continue organizing for the freedom of other incarcerated people in the next three years and after his release. We hope you all will do the same. FREE THEM ALL.

- Write to Uhuru at this address:

Uhuru B. Rowe

#1131545

Buckingham Correctional Center

PO Box 430

Dillwyn, VA 23936

- You can email Uhuru at this email address: [email protected]

His audio commentaries here: https://www.prisonradio.org/correspondent/uhuru-rowe/#section-contact-info