TTT Vol. 13 #3

PART’s Perspective: Police, Protests, and People’s Power

Building Communities of Resistance

by Michael Novick

The smoke has cleared, figuratively speaking, from the Republican and Democratic Party conventions in Philadelphia and Los Angeles. With, if not the whole world, then at least a substantial audience watching, major demonstrations were held on successive days at both venues; both cities were subjected to a virtual state of siege by local and state police forces. Philadelphia and even more so Los Angeles were marked by significant participation in the protests by local people, young people and people of color, especially as compared with the prior Seattle and DC protests targeting corporate globalization.

In Philadelphia, more so than L.A., police resorted to pre-emptive raids, mass arrests and violence. However, a massive legal unity march in Philadelphia was unmolested, and the Kensington Welfare Rights Union led a second, non-permitted march which defied police pressure and threats to carry out its protest rally successfully. However, for the August 1 RNC actions targeting the criminal justice system, including police brutality, the death penalty and the case of Mumia Abu-Jamal, the Philly cops took the gloves off.

Armed with fraudulent “intelligence” from private right wing counter-insurgency guru John Rees, the police raided the puppet-making center. They picked up people on the street, such as an organizer with the Ruckus Society, whose crime was talking on a cell phone, and held them for astronomical bails. They made mass arrests and held people under inhumane conditions, and resisted campaigns to drop or lower the charges.

By comparison, in Los Angeles, the police concentrated on a show of force, making relatively few arrests. The L.A. cops maintained hands off a large, spirited rally for Mumia Abu-Jamal the day before the Democratic Convention opened, but pulled the plug on a legal, permitted evening unity rally the first night that featured Rage Against the Machine and Ozomatli. On the pretext of some Black Bloc-ers tossing empty water bottles over the 14-foot fence that surrounded Staples Center, the cops issued an order to 15,000 people to disperse, then with horses drove back into the protest area those who actually tried to leave.

The cops unleashed a barrage of flash-bangs, pepper spray and ‘rubber’ bullets, shooting people in the head, the back and the chest, sending homeless organizer Ted Hayes to the hospital, shooting up numerous clearly-marked legal observers, and both on that first night and in subsequent confrontations, targeting media personnel. The police attempted to cover this action up by simultaneously shutting down the nearby Independent Media Center, which was scheduled to uplink its uncensored coverage to a satellite, on the flimsy pretext of a (non-existent) bomb threat.

A number of law suits resulted, but more significantly, two major actions were carried out on Wednesday August 16 despite the police effort to intimidate protestors. One, a civil disobedience action directed at police brutality, briefly shut the scandal-ridden LAPD Rampart Division station. The second, a march and rally opposing police brutality, mass incarceration and the death penalty, and calling for freedom for all political prisoners, drew thousands to Pershing Square and marched on Parker Center, LAPD headquarters, flanked by as many thousands of cops.

People around downtown, especially those from Latin American countries that had lived under police states, watched with looks of shame, fear and amazement at this domestic recreation of a state of siege. But demonstrators refused to be intimidated. A youth march headed back through downtown to Staples Center, where the police tried to split the demonstrators up, trapping some inside the expanded protest pit where the police attack had taken place on Monday night.

A televised stand-off ensued, from which the cops eventually stood down. The protesters got their comrades back from behind the police lines. Some marched off to MacArthur Park, near the Direct Action Network Convergence Center; others marched back to Pershing Square for an impromptu wrap-up open mike gathering.

On the final night, protesters again defied police orders to stage an unpermitted march through downtown to the Twin Towers central men’s jail run by the L.A. sheriffs, where some hundred-odd protesters who had been arrested at a series of rallies, including animal rights activists, defenders of the Uwa in Colombia, and Critical Mass bike-riders, as well as those who carried out the CD action at Rampart, were carrying out jail solidarity. A vigil was maintained outside the jail through the week until the City Attorney agreed to lower the charges to infractions and release the demonstrators for time served. A few cases remain, including felony charges against a neighborhood youth whom the cops claim tossed a bottle at them when they set up a skirmish line outside the Convergence Center. (Under a federal court order enjoining them from preemptively entering the Center, the LAPD could not emulate their Philadelphia peers, and withdrew after baring their teeth).

What can we learn about the state of our movement, the political strength of the forces of repression and exploitation, and about the necessary directions and steps by which to move forward?

THE STATE OF THE STATE

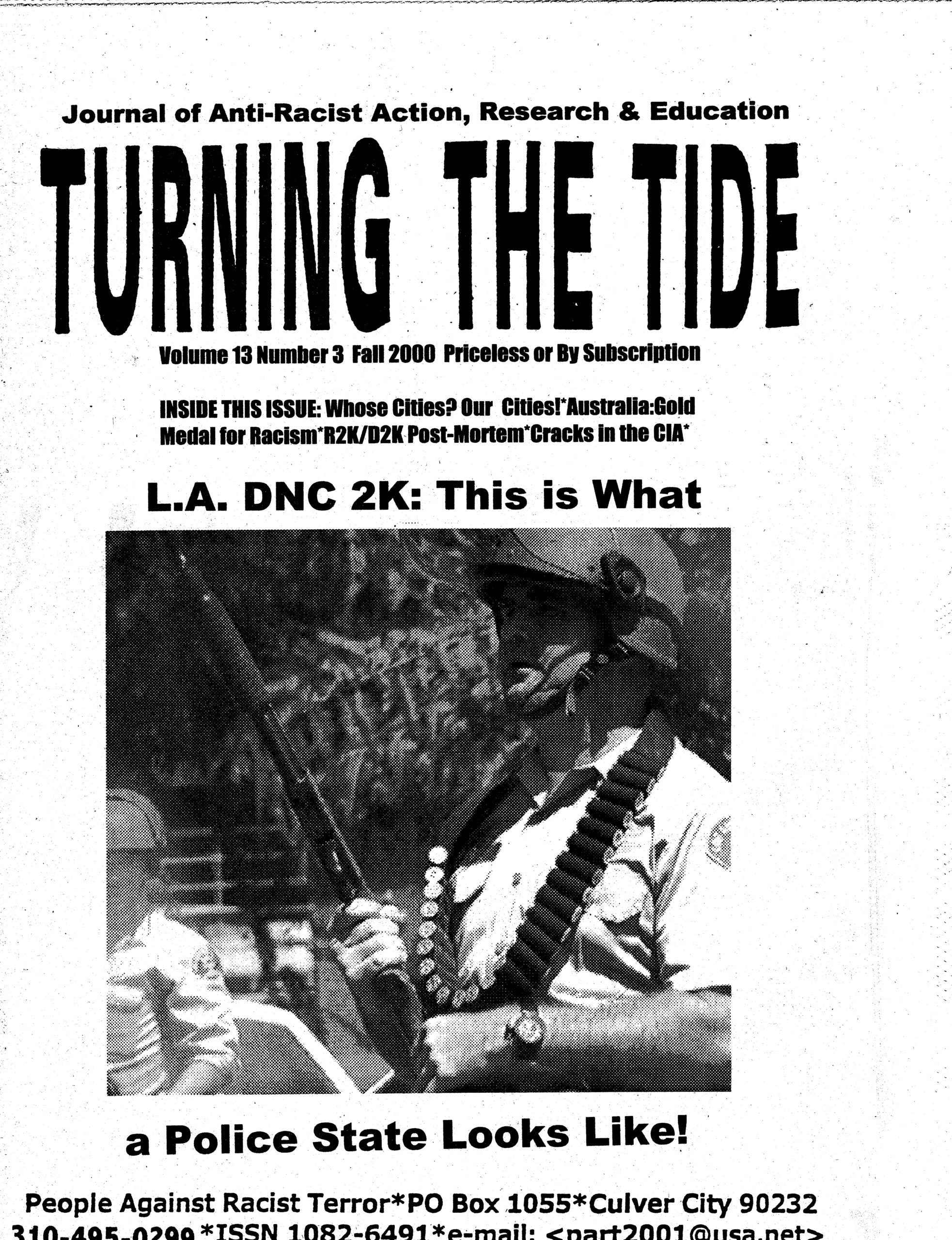

First, a clear understanding of how to view the police repression is necessary. It certainly felt true, marching through downtown L.A. surrounded by cops, to chant, “This is what a police state looks like!” However, we should be clear that the police were in fact operating under significant legal and political constraints.

They had massive personnel, vast quantities of equipment providing a stunning visual manifestation of the extent of militarization of the police that has steadily escalated on a national level during the Clinton years but except for Monday night, they did not have the marching orders for unrestrained violence. In point of fact, day in and day out, those thousands of cops are deployed around the city, particularly in communities of color and they have relative carte blanche still to use brutality and deadly force to carry out their mission of serving the wealthy and protecting the capitalist-colonialist system. The violence and abuse they did carry out against demonstrators must be understood in the context of that larger dynamic.

The LAPD was hoping to rehabilitate its tarnished reputation and rebuild its coalition of political support with its actions during the DNC. Its inability to do so on its own terms can be measured by the fact that in the wake of the new violence during the DNC, the Mayor, police chief and City Council finally and reluctantly caved in and agreed to reach a consent decree with the Justice Department. This calls for federal court oversight and an outside monitor to supervise LAPD compliance with a series of reforms to overcome a ‘pattern and practice’ of racism and civil rights violations.

It does not diminish the seriousness of the complaints and suits being brought against the LAPD for their handling of the demonstrations to recognize that they must be taken up in the context of an ongoing struggle against police racism and brutality and for community control of the police. This is equally true in Philadelphia.

The Philly PD and the LAPD have proven themselves to be thoroughly corrupt, violent, racist institutions with blood on their hands, yet they continue to enjoy the political support of the political, corporate and civic elites in their cities. It is this support which we must challenge by splitting off the mass base of people, even in communities of color and certainly in more privileged areas, who will always give the cops ‘the benefit of the doubt.’ We must continue to expose the systemic nature of police abuse and racism.

We must alert people to the inadequacy of elite ‘reforms’ such as the DOJ-LAPD consent decree and ‘community policing,’ actually an aspect of police militarization in that it is the application to domestic law enforcement of the military’s use of psychological operations to control the thinking of a population or enemy. And finally, we must redouble our efforts to build a grassroots base for direct action against police brutality, to exert community control of the police through such mechanisms as Copwatch vigilance against police abuse.

THE STATE OF THE MOVEMENT

What do the Philadelphia and Los Angeles demonstrations tell us about the state of our movements? First of all, we are a movement of protestors — no shame in that, in fact it is a significant positive development that a consciousness of opposition and resistance to imperialism and its ugly realities is taking root in a new generation. Compare the relatively feeble and unnoticed protests against the Republican and Democratic Conventions four years ago to the rousing and numerous rallies, the convergence of organizers and themes this year, to see how far we have come.

But let that be the vantage point from which we can see more clearly how much farther we have to go. We need to develop into organizers, to sink organic roots. In the context of US society, this means a much more concerted attack on white supremacy, capitalism and colonialism their institutionalized manifestations and their internalization within the movements and within exploited and oppressed people.

Second, we can see that our movements have made some progress in overcoming weaknesses that must be overcome if we are to move forward. Although L.A. and Philly had much stronger and more visible participation and leadership from people of color, the central organizing coalitions still had many of the same weaknesses, based in a white left, that were manifested in Seattle and D.C. protests against the WTO and the IMF.

What some complained about as a ‘lack of focus’ in the L.A. demonstrations was in fact a partly successful effort to broaden out to demands that reflected the impact of the empire on communities of color and working people in the U.S. However, this forward motion was definitely incomplete. The culture of the meetings, the centers and the protest rallies themselves is still comfortable only for a relatively narrow sector. More significantly, the demands that are raised and the unities that are reached rarely strike out squarely and unequivocally against racism or colonialism, nor are they based on the self-determination and leadership of oppressed people. Thus, one of the most significant protests in L.A. was hardly noticed or supported by the “official” coalitions and media activists a Black-initiated and led rally for reparations on Tuesday morning.

Moreover, as the movement does grow, the ills of sectarianism and vanguardism reinforced by a racism that refuses to recognize or support the need for autonomous self-determined leadership and organizing by communities of color come into sharp focus. In both Philadelphia and L.A. (and in nearby DNC organizing committees such as San Diego), the International Socialist Organization attempted to substitute its cadre operation for the egalitarian and democratic consensus mechanisms of the burgeoning protest movement. They burrowed into outreach committees, using contacts obtained for building the protests for purposes of recruiting new cadre and candidates for their own organization.

Philadelphia activists were especially critical of an ISO “affinity group” which reneged on its commitment to diversionary support work in the face of police attack. In L.A., ISO cadre preempted the organized monitoring of the Thursday night protest and used their self-proclaimed status to try to isolate and provoke anarchist members of the Black Bloc.

In both Philadelphia and L.A., the RCP played a sectarian role around demonstrations focused on the criminal justice system. In Philadelphia, Refuse and Resist did an end run around a previously called and building coalition for direct action and non-violent civil disobedience initiated by NY-DAN. In L.A., RCP cadre from within the October 22nd Coalition attempted to hijack the protest against the criminal injustice system. The RCP and PLP (Progressive Labor) engaged in a protracted sectarian struggle, turning many independent people off to the coalition meetings.

Even more significantly, the RCP led in at first opposing raising the demand to free political prisoners. While they later reversed themselves, they persisted throughout in trying to reduce the action to a protest against police brutality, a “launching pad for October 22nd” as they repeatedly called it. The political basis of this is a rejection of self-determination for Black, Chicano-Mexicano, Asian and Native people. Although the demonstration was ultimately fairly successful, its potential was never fully realized because of the RCP’s hegemonic strategy.

Significant Black and Chicano-Mexicano forces were put off from participation, and the RCP succeeded in alienating prison activists that attempted to participate by insisting on its formulations about prisons. RCP reduced the issue to a subset of police brutality and ‘criminalization,’ while ignoring all the concrete issues of repression of prisoners and their families, mass incarceration, and prison labor and privatization that have been motivating prisoners and their families into building a new mass movement.

Another key factor was that the RCP continued right through the demonstration to posture about what kind of action or resistance it was going to engage in. It insisted on a separate ‘youth’ march called under the auspices of the Youth Student Network of October 22nd (which in practice proved indistinguishable from the overall coalition from which it intended to split off) so that it could put out provocative rhetoric and preserve its ‘revolutionary’ credentials.

Sectarianism was not restricted to those two groups of course. The attitude of the central D2KLA Coalition towards the August 16 March for Justice Coalition which included the RCP was problematic at best. There were problems of red-baiting and animosity towards the socialist and communist left within what purported to be a united front the D2KLA coalition/network was unfortunately neither fish nor fowl; not a traditional coalition with a clear, defined unity, organizational structure and leadership, not the free-flowing, consensus-seeking organic direct democracy of Seattle.

Had the overall coalition united more enthusiastically with its own call for a day of action focused on criminal injustice issues, there would have been a chance to build a coalition for that day large enough and broad enough that the RCP would have been only one minor player, less capable of packing meetings and whipsawing other participants. But the D2KLA network stayed closer to the ‘fair trade’ and anti-corporate themes that it started with and felt less invested in a demonstration against the racist impact of the organs of state repression.

There was also a major weakness evidenced by some of the participants and organizers to fall in with a stigmatization or even a criminalization of more militant protesters, particularly self-professed anarchists and members of the Black Bloc. This was less pronounced in L.A. where issues of property destruction were virtually non-existent but the expressed opinion of people from Ruckus and other organizations, attempting to distinguish themselves from ‘violent’ protesters who were apparently ‘deserving’ of arrest was a manifestation of class and national/racial privilege. One thing L.A. made perfectly clear, in the wake of Seattle, DC, and Philadelphia is that ‘violence’ is still very much a monopoly of the state, and it is this police state apparatus and military defending the empire which is the main source of violence, including the violence of hunger, sweated labor, and prison.

WHAT IS TO BE DONE?

Finally, what can we learn about the direction and strategies our movement must embark on to overcome these weaknesses and take further advantages of the contradictions the state and the ruling elite find themselves in?

Above all, we must get beyond mobilization mode. Maintaining an endless stream of reactive protests to one elite institution after another is a recipe for disaster, burn-out, and creating a free-floating and rootless culture of protest that will ultimately prove powerless against the imperialist system. We have gathered forces to begin to go beyond that. Much more so in communities of color than among white leftists, student radicals and anarchist counter-cultural scenes, revolutionary-minded organizers are sinking roots in grassroots communities and in workplaces. Anti-racist Euro-Americans must identify the lower working class sectors of white people and youth in high schools and colleges who are prepared to unite with oppressed people.

There are a number of issues around which anti-racists must begin to develop community-rooted, community-accountable organizations that respond to anti-imperialist leadership from organizers of color. Certainly issues around the criminal justice system are one such nexus. A significant development of the August 1 actions in Philadelphia and the August 16 rally in L.A. is that they linked together questions of police brutality, prisons and mass incarceration, the death penalty, and the struggle to free political prisoners. The organic, real world connections among these issues means that uniting efforts around them should strengthen our ability to make gains on all of them.

There is in fact a similar dynamic at play around all four issues. The release of the Puerto Rican prisoners, the growing movement for Mumia, the momentum for Peltier’s freedom, make it clear that there has been a significant massification of the struggle to free political prisoners. Similarly, sentiment against the death penalty has been growing far and wide in the population. Mass incarceration has made prison issues a mass question. And ugly examples of police brutality, as well as exposures of racial profiling and police criminality and murders that won’t again, have made the struggle against police abuse one of the hottest political questions in city after city, even if the presidential candidates are virtually silent (except to announce their support of or claim support from the cops).

What’s more, the inter-connection of these issues is educating people broadly about the nature of this system. People who see that the imprisonment of freedom fighters like Geronimo ji Jaga is what gave the system the capacity to go from locking up 200,000 people to penning 2,000,000 see a clear interest in freeing political prisoners. People who understand that the mistreatment and interminable sentences that were once reserved for political dissident and revolutionary soldiers is now the order of the day for tens of thousands of social prisoners can be drawn into community based organizing that goes beyond a call to conscience.

At the same time, around all these issues, the state is making it clear that it will not yield. Democrats like Gray Davis or Republicans like Tom Ridge, Gore or Bush at the presidential level persist in supporting more and better-armed cops, swifter executions, bigger prisons as a strategy for maintaining social control and political support. Unless we persevere, go farther and deeper in building effective resistance, the forces of repression will regain momentum and the upper hand on these issues.

We need to recognize where people are at in order to move further. For instance, the demonstrations at the Republican Convention were generally speaking, either larger or more militant than the corresponding ones at the Democratic Convention. This was not due to the relative qualities of the organizers or the geographic location of the two cities, but because significant sectors of the communities that should form the base of a protest movement are in fact wedded to the Democratic Party.

This was certainly true of organized labor, which was inside the DNC rather than on the streets, in the main, and is also true of substantial portions of communities of color. To denounce the labor bureaucrats and the sell-out, vende-patria politicians is useless without patient grass-roots organizing and base-building for direct community based action on the issues that matter to people education and the schools, decent housing, food and health care, and end to police brutality not to raise demands on the system or requests to the politicos, but to build the community power of working and oppressed people that can begin to remake the world from below.